Von Jamal Hassan, Backend Developer bei Java Fleet Systems Consulting

Mit Einblicken von Elyndra Valen (Senior Dev) und Nova Trent (Junior Dev)

Schwierigkeit: 🔴 Fortgeschritten

Lesezeit: 45 Minuten

Voraussetzungen: Tag 8 (Multithreading Basics)

Kurs: Java Erweiterte Techniken – Tag 9 von 10

📖 Java Erweiterte Techniken – Alle Tage

📍 Du bist hier: Tag 9

⚡ Das Wichtigste in 30 Sekunden

Dein Problem: Mehrere Threads greifen auf dieselben Daten zu. Chaos entsteht: Race Conditions, inkonsistente Daten, schwer zu findende Bugs.

Die Lösung: Synchronisation – kontrollierter Zugriff auf gemeinsame Ressourcen.

Heute lernst du:

- ✅ Race Conditions verstehen und vermeiden

- ✅

synchronizedBlöcke und Methoden - ✅

volatilefür Sichtbarkeit - ✅

java.util.concurrentLocks - ✅ Atomic-Klassen für lockfreie Operationen

- ✅ Thread-sichere Collections

- ✅ Deadlocks erkennen und vermeiden

👋 Jamal: „Der unsichtbare Bug“

Hi! 👋

Jamal hier für den anspruchsvollsten Tag unseres Kurses. Synchronisation ist das, was Multithreading richtig schwer macht.

Das Problem:

public class Konto {

private int kontostand = 1000;

public void abheben(int betrag) {

if (kontostand >= betrag) {

// Thread A ist hier... wechselt zu Thread B

kontostand -= betrag;

}

}

}

// Zwei Threads heben gleichzeitig 800€ ab

// Kontostand: 1000€

// Thread A prüft: 1000 >= 800? Ja!

// Thread B prüft: 1000 >= 800? Ja! (noch nicht abgezogen!)

// Thread A: kontostand = 1000 - 800 = 200

// Thread B: kontostand = 200 - 800 = -600 // ÜBERZOGEN!

Das ist eine Race Condition – das Ergebnis hängt davon ab, welcher Thread zuerst fertig ist.

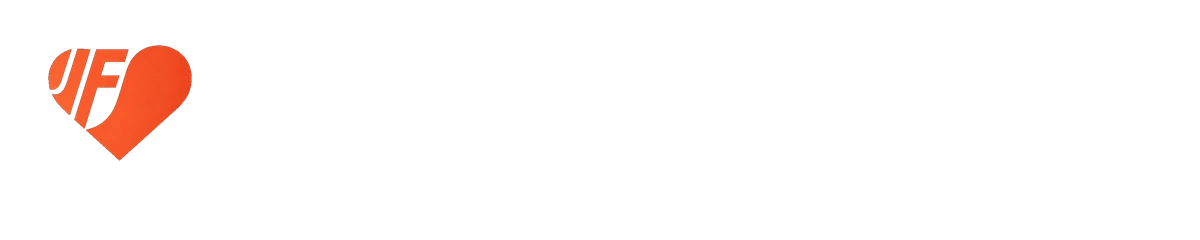

🖼️ Race Condition visualisiert

Abbildung 1: Zwei Threads kämpfen um dieselbe Ressource

🟢 GRUNDLAGEN

Das synchronized Keyword

Methode synchronisieren:

public class Konto {

private int kontostand = 1000;

public synchronized void abheben(int betrag) {

if (kontostand >= betrag) {

kontostand -= betrag;

}

}

public synchronized void einzahlen(int betrag) {

kontostand += betrag;

}

public synchronized int getKontostand() {

return kontostand;

}

}

Was passiert?

- Nur ein Thread kann gleichzeitig eine synchronized-Methode des Objekts ausführen

- Andere Threads warten (blockieren)

- Lock wird automatisch freigegeben am Ende der Methode

Synchronized Block

Feingranularer als synchronized-Methoden:

public class Konto {

private int kontostand = 1000;

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void abheben(int betrag) {

// Code VOR dem kritischen Bereich (kann parallel laufen)

System.out.println("Bereite Abhebung vor...");

synchronized (lock) {

// NUR DIESER BEREICH ist geschützt

if (kontostand >= betrag) {

kontostand -= betrag;

}

}

// Code NACH dem kritischen Bereich

System.out.println("Abhebung verarbeitet");

}

}

Warum ein separates Lock-Objekt?

synchronized(this)lockt das ganze Objekt- Separates Lock = feinere Kontrolle

- Mehrere unabhängige Locks möglich

Worauf locken?

// Auf this locken (wie synchronized-Methode)

synchronized (this) {

// ...

}

// Auf separates Objekt locken (empfohlen)

private final Object lock = new Object();

synchronized (lock) {

// ...

}

// Auf Klasse locken (für statische Methoden)

synchronized (Konto.class) {

// ...

}

// Auf die Collection selbst locken

synchronized (liste) {

liste.add(element);

}

volatile – Sichtbarkeit garantieren

public class StoppbareAufgabe implements Runnable {

private volatile boolean running = true;

public void stop() {

running = false; // Änderung sofort für alle Threads sichtbar

}

@Override

public void run() {

while (running) {

// Arbeite...

}

System.out.println("Gestoppt!");

}

}

Ohne volatile:

- Jeder Thread hat eigenen Cache

- Änderungen möglicherweise nicht sichtbar

- Thread läuft endlos weiter!

Mit volatile:

- Schreiboperationen sofort im Hauptspeicher

- Leseoperationen immer aus Hauptspeicher

- Aber: Keine Atomarität!

count++ist trotzdem nicht thread-safe

🟡 PROFESSIONALS

java.util.concurrent.locks

Mehr Kontrolle als synchronized:

import java.util.concurrent.locks.*;

public class Konto {

private int kontostand = 1000;

private final ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

public void abheben(int betrag) {

lock.lock(); // Lock erwerben

try {

if (kontostand >= betrag) {

kontostand -= betrag;

}

} finally {

lock.unlock(); // IMMER in finally!

}

}

// Mit Timeout - blockiert nicht ewig

public boolean abhebenMitTimeout(int betrag) throws InterruptedException {

if (lock.tryLock(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS)) {

try {

if (kontostand >= betrag) {

kontostand -= betrag;

return true;

}

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

}

return false; // Lock nicht bekommen

}

}

Vorteile gegenüber synchronized:

tryLock()– Versuch ohne BlockierentryLock(timeout)– Versuch mit TimeoutlockInterruptibly()– Unterbrechbar- Fairness-Option:

new ReentrantLock(true)

ReadWriteLock – Lesen parallel, Schreiben exklusiv

import java.util.concurrent.locks.*;

public class Cache {

private final Map<String, String> data = new HashMap<>();

private final ReadWriteLock rwLock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock();

private final Lock readLock = rwLock.readLock();

private final Lock writeLock = rwLock.writeLock();

public String get(String key) {

readLock.lock(); // Mehrere Leser parallel OK

try {

return data.get(key);

} finally {

readLock.unlock();

}

}

public void put(String key, String value) {

writeLock.lock(); // Exklusiv - keine anderen Leser/Schreiber

try {

data.put(key, value);

} finally {

writeLock.unlock();

}

}

}

Wann nutzen?

- Viele Lesezugriffe, wenige Schreibzugriffe

- Lesen ist teuer (z.B. Berechnung)

Atomic-Klassen – Lockfrei und schnell

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.*;

public class Zaehler {

private AtomicInteger count = new AtomicInteger(0);

public void increment() {

count.incrementAndGet(); // Thread-safe ohne Lock!

}

public int get() {

return count.get();

}

}

// Weitere Atomic-Klassen:

AtomicLong atomicLong = new AtomicLong(0);

AtomicBoolean atomicBool = new AtomicBoolean(false);

AtomicReference<String> atomicRef = new AtomicReference<>("initial");

// Nützliche Methoden:

int oldValue = count.getAndIncrement(); // Erst lesen, dann erhöhen

int newValue = count.incrementAndGet(); // Erst erhöhen, dann lesen

count.compareAndSet(expected, newValue); // CAS-Operation

count.updateAndGet(x -> x * 2); // Mit Lambda

Wann Atomic statt Lock?

- Einfache Operationen (Zähler, Flags)

- Hohe Parallelität

- Performance kritisch

Thread-sichere Collections

import java.util.concurrent.*;

// ===== STATT ArrayList =====

List<String> safeList = new CopyOnWriteArrayList<>();

// Gut für: Viele Leser, wenige Schreiber

// Nachteil: Kopiert bei jedem Schreiben

// ===== STATT HashSet =====

Set<String> safeSet = ConcurrentHashMap.newKeySet();

// Oder:

Set<String> safeSet2 = new CopyOnWriteArraySet<>();

// ===== STATT HashMap =====

Map<String, Integer> safeMap = new ConcurrentHashMap<>();

// Hochperformant, feinkörnige Locks

// ===== Queues =====

BlockingQueue<String> queue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

queue.put("Element"); // Blockiert wenn voll

String item = queue.take(); // Blockiert wenn leer

// Mit Timeout:

queue.offer("Element", 1, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

String item2 = queue.poll(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS);

Faustregeln:

| Situation | Empfehlung |

|---|---|

| Map mit vielen Zugriffen | ConcurrentHashMap |

| Liste, meist lesen | CopyOnWriteArrayList |

| Liste, viel schreiben | Collections.synchronizedList() |

| Producer-Consumer | BlockingQueue |

wait() und notify() – Thread-Kommunikation

public class ProducerConsumer {

private final Queue<Integer> queue = new LinkedList<>();

private final int MAX_SIZE = 10;

public synchronized void produce(int item) throws InterruptedException {

while (queue.size() == MAX_SIZE) {

wait(); // Warte bis Platz frei

}

queue.add(item);

System.out.println("Produziert: " + item);

notifyAll(); // Wecke wartende Consumer

}

public synchronized int consume() throws InterruptedException {

while (queue.isEmpty()) {

wait(); // Warte bis Daten da

}

int item = queue.poll();

System.out.println("Konsumiert: " + item);

notifyAll(); // Wecke wartende Producer

return item;

}

}

Wichtig:

wait()undnotify()nur in synchronized!- Immer in

while-Schleife prüfen (spurious wakeups) notifyAll()weckt alle,notify()nur einen

🔵 BONUS

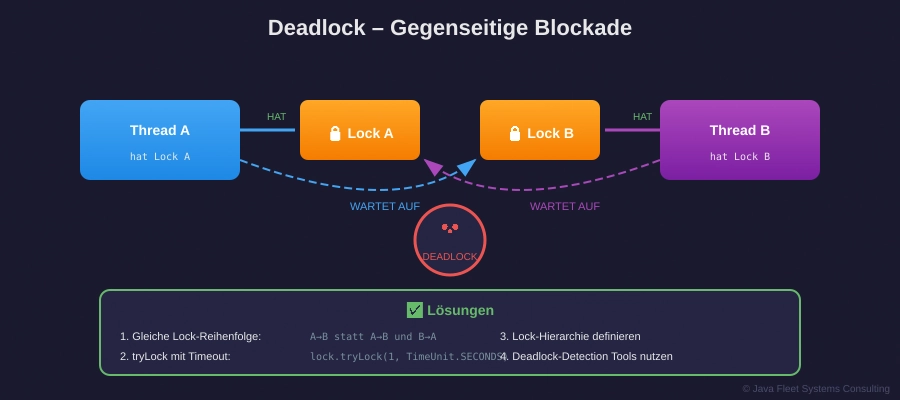

Deadlocks erkennen und vermeiden

Abbildung 2: Zwei Threads blockieren sich gegenseitig

// DEADLOCK-GEFAHR!

public class DeadlockBeispiel {

private final Object lockA = new Object();

private final Object lockB = new Object();

public void methode1() {

synchronized (lockA) {

System.out.println("Thread 1: hat Lock A");

synchronized (lockB) { // Wartet auf Lock B

System.out.println("Thread 1: hat Lock B");

}

}

}

public void methode2() {

synchronized (lockB) { // Hat Lock B

System.out.println("Thread 2: hat Lock B");

synchronized (lockA) { // Wartet auf Lock A -> DEADLOCK!

System.out.println("Thread 2: hat Lock A");

}

}

}

}

Deadlock-Vermeidung:

// LÖSUNG 1: Gleiche Lock-Reihenfolge

public void methode1() {

synchronized (lockA) {

synchronized (lockB) { /* ... */ }

}

}

public void methode2() {

synchronized (lockA) { // Gleiche Reihenfolge: A dann B

synchronized (lockB) { /* ... */ }

}

}

// LÖSUNG 2: tryLock mit Timeout

public void sichereMethode() {

while (true) {

if (lockA.tryLock()) {

try {

if (lockB.tryLock()) {

try {

// Beide Locks erhalten

return;

} finally {

lockB.unlock();

}

}

} finally {

lockA.unlock();

}

}

Thread.sleep(10); // Kurz warten, neu versuchen

}

}

Semaphore – Begrenzte Ressourcen

import java.util.concurrent.Semaphore;

public class ConnectionPool {

private final Semaphore semaphore;

public ConnectionPool(int maxConnections) {

this.semaphore = new Semaphore(maxConnections);

}

public void useConnection() throws InterruptedException {

semaphore.acquire(); // Blockiert wenn keine Permits verfügbar

try {

System.out.println("Verbindung genutzt von " + Thread.currentThread().getName());

Thread.sleep(1000);

} finally {

semaphore.release(); // Permit zurückgeben

}

}

}

// Verwendung: Max 3 gleichzeitige Verbindungen

ConnectionPool pool = new ConnectionPool(3);

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

new Thread(() -> pool.useConnection()).start();

}

CountDownLatch – Auf mehrere Threads warten

import java.util.concurrent.CountDownLatch;

public class StartSignal {

public static void main(String[] args) throws InterruptedException {

int anzahlWorker = 5;

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(anzahlWorker);

for (int i = 0; i < anzahlWorker; i++) {

final int id = i;

new Thread(() -> {

System.out.println("Worker " + id + " arbeitet...");

try { Thread.sleep(1000); } catch (InterruptedException e) {}

System.out.println("Worker " + id + " fertig!");

latch.countDown(); // Zähler -1

}).start();

}

System.out.println("Warte auf alle Worker...");

latch.await(); // Blockiert bis Zähler = 0

System.out.println("Alle Worker fertig!");

}

}

💬 Real Talk: Synchronisations-Fallen

Java Fleet Büro, Montag 09:00. Debugging-Session.

Nova: „Jamal, mein Zähler zeigt immer falsche Werte an!“

private int counter = 0;

public void increment() {

counter++; // NICHT thread-safe!

}

Jamal: „counter++ ist drei Operationen: Lesen, Erhöhen, Schreiben. Dazwischen kann ein anderer Thread dazwischenfunken.“

// Lösung 1: synchronized

public synchronized void increment() {

counter++;

}

// Lösung 2: AtomicInteger (besser!)

private AtomicInteger counter = new AtomicInteger(0);

public void increment() {

counter.incrementAndGet();

}

Nova: „Und mein Programm hängt manchmal einfach…“

Elyndra: schaut auf den Code „Deadlock. Du lockst in unterschiedlicher Reihenfolge.“

// Thread 1: lockA -> lockB // Thread 2: lockB -> lockA // -> DEADLOCK!

Elyndra: „Regel: Immer in derselben Reihenfolge locken. Oder tryLock() mit Timeout verwenden.“

Jamal: „Und denkt dran: volatile macht Variablen sichtbar, aber nicht atomar!“

private volatile int count = 0; count++; // IMMER NOCH NICHT THREAD-SAFE!

❓ FAQ

Frage 1: synchronized Methode vs. Block?

synchronized Methode:

- Einfacher zu lesen

- Lockt auf

this(oder Klasse bei static) - Ganze Methode ist kritischer Bereich

synchronized Block:

- Feingranularer

- Kann auf beliebiges Objekt locken

- Nur Teil der Methode ist kritisch

Frage 2: Wann Lock, wann synchronized?

| synchronized | ReentrantLock |

|---|---|

| Einfacher | Mehr Features |

| Automatisch unlock | Manuell unlock (try-finally!) |

| Kein Timeout | tryLock mit Timeout |

| Nicht unterbrechbar | lockInterruptibly() |

Faustregel: synchronized für einfache Fälle, Lock für komplexe Anforderungen.

Frage 3: Ist ConcurrentHashMap immer thread-safe?

Einzelne Operationen: Ja!

map.put("key", "value"); // Thread-safe

map.get("key"); // Thread-safe

Zusammengesetzte Operationen: Nein!

// NICHT thread-safe:

if (!map.containsKey("key")) {

map.put("key", "value");

}

// Thread-safe Alternative:

map.putIfAbsent("key", "value");

map.computeIfAbsent("key", k -> "value");

Frage 4: Was ist ein „spurious wakeup“?

Ein Thread kann aus wait() aufwachen, ohne dass notify() aufgerufen wurde. Deshalb immer in while-Schleife prüfen:

// FALSCH:

if (queue.isEmpty()) {

wait();

}

// RICHTIG:

while (queue.isEmpty()) {

wait();

}

Frage 5: Bernd sagt, er braucht keine Synchronisation?

seufz Bernds Code läuft auf einem Kern. In Produktion mit 32 Kernen… Boom! 💥

🔍 „behind the code“ oder „in my feels“? Die echten Geschichten findest du, wenn du weißt wo du suchen musst…

🎁 Cheat Sheet

🟢 synchronized

// Methode

public synchronized void methode() { }

// Block

synchronized (lock) { }

// Auf this

synchronized (this) { }

// Auf Klasse

synchronized (MeineKlasse.class) { }

🟡 Locks

ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

lock.lock();

try { /* ... */ } finally { lock.unlock(); }

// Mit Timeout

if (lock.tryLock(1, TimeUnit.SECONDS)) { }

// ReadWriteLock

ReadWriteLock rwLock = new ReentrantReadWriteLock();

rwLock.readLock().lock(); // Mehrere Leser OK

rwLock.writeLock().lock(); // Exklusiv

🔵 Atomic

AtomicInteger count = new AtomicInteger(0); count.incrementAndGet(); count.getAndIncrement(); count.compareAndSet(expected, newValue); count.updateAndGet(x -> x * 2);

🟣 Collections

ConcurrentHashMap<K, V> // Thread-safe Map CopyOnWriteArrayList<E> // Viele Leser BlockingQueue<E> // Producer-Consumer Collections.synchronizedList() // Wrapper

🎨 Challenge für dich!

🟢 Level 1 – Einsteiger

- [ ] Mache einen einfachen Zähler thread-safe mit synchronized

- [ ] Verwende AtomicInteger für einen Zähler

- [ ] Erstelle eine thread-safe Getter/Setter Klasse

Geschätzte Zeit: 30-40 Minuten

🟡 Level 2 – Fortgeschritten

- [ ] Implementiere einen Thread-safe Stack mit Lock

- [ ] Nutze ReadWriteLock für einen Cache

- [ ] Baue einen Producer-Consumer mit BlockingQueue

Geschätzte Zeit: 45-60 Minuten

🔵 Level 3 – Profi

- [ ] Finde und behebe einen Deadlock

- [ ] Implementiere einen ConnectionPool mit Semaphore

- [ ] Nutze CountDownLatch für parallele Initialisierung

Geschätzte Zeit: 60-90 Minuten

Java Erweiterte Techniken - Tag 9

Multithreading Synchronisation

📦 Downloads

| Projekt | Für wen? | Download |

|---|---|---|

| tag09-synchronisation-starter.zip | 🟢 Mit TODOs | ⬇️ Download |

| tag09-synchronisation-complete.zip | 🟡 Musterlösung | ⬇️ Download |

🔗 Weiterführende Links

🇩🇪 Deutsch

| Ressource | Beschreibung |

|---|---|

| Rheinwerk: Threads | Synchronisation Kapitel |

🇬🇧 Englisch

| Ressource | Beschreibung | Level |

|---|---|---|

| Oracle: Synchronization | Offizielle Doku | 🟡 |

| Baeldung: java.util.concurrent | Praxisbeispiele | 🟡 |

| Java Concurrency in Practice | Das Standardwerk | 🔴 |

👋 Geschafft! 🎉

Was du heute gelernt hast:

✅ Race Conditions verstehen und vermeiden

✅ synchronized für gegenseitigen Ausschluss

✅ volatile für Sichtbarkeit

✅ ReentrantLock und ReadWriteLock

✅ Atomic-Klassen für lockfreie Operationen

✅ Thread-sichere Collections

✅ Deadlocks erkennen und vermeiden

Fragen? jamal.hassan@java-developer.online

📖 Weiter geht’s!

← Vorheriger Tag: Tag 8: Annotations & Multithreading Basics

→ Nächster Tag: Tag 10: Netzwerkprogrammierung

Tags: #Java #Multithreading #Synchronisation #Concurrency #ThreadSafety #Tutorial

📚 Das könnte dich auch interessieren

© 2025 Java Fleet Systems Consulting | java-developer.online